Some time ago, at a meeting of Forética at the headquarters of the General Council of ONCE, my friend Fernando Riaño reminded me of an unforgettable episode:

It was 1995 when Bill Gates visited ONCE to learn first-hand about an organization he had never heard of. As he started a demonstration of Windows, they turned off his screen and said:

- "Use it now, Mr. Gates, use it."

That gesture, as simple as it was significant, made him understand what it meant to face technology without seeing it. A few minutes were enough to ignite a new awareness in him and in Microsoft: accessibility could no longer be an add-on, but a design principle.

I was fortunate to later work on the integration of a Braille driver for Windows 98, to teach "C++ programming" classes for blind people and, decades later, to be part of the Advisory Council for Digital Talent of the ONCE Foundation. Since then I have not stopped thinking about this idea: when we design for those who encounter the most barriers, we improve everyone's experience.

From accessibility to strategic design

Thirty years later, that lesson is still valid. But today we have a tool that multiplies its reach: artificial intelligence.

In particular, generative AI is transforming the way people with disabilities interact with the world. And it is doing so not as a layer of assistance, but as a new language of inclusion. Where there was dependence before, there is now autonomy; where there were physical or sensory barriers, there is translation, synthesis or prediction.

The impact is beginning to be tangible and examples would make this article too long. To cite a few:

- Seeing AI launched by Microsoft in 2017, was one of the first accessible AI applications: it uses computer vision to recognize text, objects, faces and describe aloud everything the camera "sees" to a blind person in real time, giving them greater autonomy.

- Be My Eyes launched Be My AI, a visual assistant based on GPT-4 that allows a blind person to "see" the content of an image and ask questions in real time.

- The Speech Accessibility Project driven by Microsoft, Apple, Google, Amazon and Meta, is training models to understand voices with non-standard pronunciations - people with ALS, cerebral palsy or Down syndrome - improving speech recognition for those traditionally left out of algorithms.

- In the work environment, Copilot helps employees with dyslexia or partial deafness to write, transcribe and participate in meetings with full autonomy (e.g. by generating instant captions).

- In education, a study by the University of Michigan (2025, Frontiers in Physiology) used generative AI to adapt physical activity routines to children with autism and ADHD. The results were clear: families improved in understanding and adherence, and cognitive and communication barriers were reduced by 60%.

These examples are not technological demonstrations: they are leaps of dignity. They show how AI can give time, voice and confidence back to millions of people.

The "curb effect": when designing for the extreme makes everything better

In the 1970s, a group of disability rights activists in Berkeley, California, got the city to build the first sidewalks ramps. Initially designed for wheelchair users, the next day they were also being used by parents with strollers, travelers with suitcases and cyclists. This phenomenon is known as the "curb-cut effect": what is designed for accessibility ends up benefiting everyone (and particularly those of us with a temporary disability).

This principle is constantly repeated in the innovation that surrounds us every day:

- Automatic subtitles were born for deaf people or people with hearing loss; today we all use them in airports or in social networks (in my case, always, when I watch movies in original version).

- Voice control was designed for people with reduced mobility; today we use it universally, while driving or cooking.

- Reading aloud, text simplification or intelligent summaries benefit both people with dyslexia and any professional with information overload.

- The background blur feature in Teams was created to improve focus on the speaker and reduce visual distractions for people with low vision or sensitivity to stimuli - and today it is used by everyone to maintain privacy or better concentrate in meetings.

It is clear: accessibility properly understood is not a cost, it is a competitive advantage. An Accenture report ("The Disability Inclusion Advantage") showed that the most advanced companies in disability inclusion outperform their peers in revenue (average 28% higher), productivity (30% higher margins) and, not least, innovation. And this is no coincidence: designing for all expands the market, builds loyalty (employees and customers) and improves product quality.

Responsible AI as a lever for inclusion

El reto ahora es escalar con confianza. No digo nada nuevo: la IA puede abrir puertas, o levantar muros invisibles. Si entrenamos modelos sin datos realmente diversos —imágenes con bastones blancos, voces atípicas, contextos de baja visión o movilidad—, acabamos construyendo sistemas que no ven ni escuchan a parte de la sociedad.

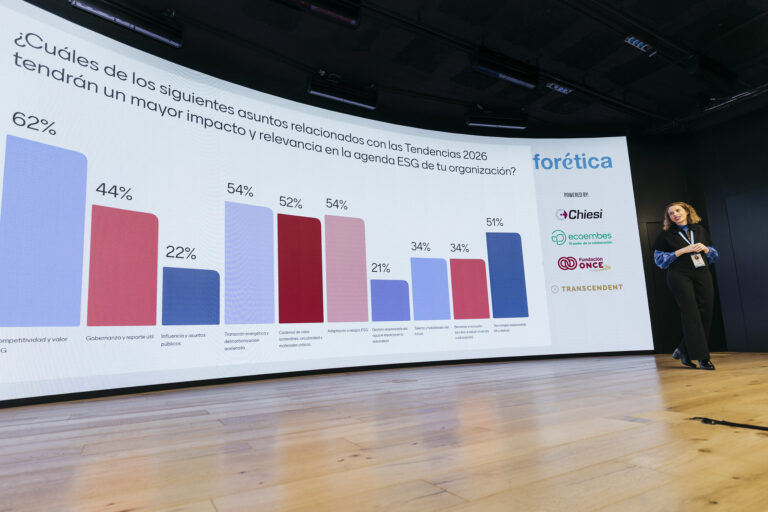

At Forética, we approach it from a governance perspective. Our Forética's Manifesto on Responsible and Sustainable AI (2025) sets out five clear principles: transparency, equity, security, environmental impact and ethical governance. They are the pillars for an inclusive, traceable and fair AI that aligns innovation with human dignity. And, at the same time, they are a strategic opportunity for those who want to lead with purpose: to move from PowerPoint to practice and integrate accessibility into the culture of design, data and decision making.

Spain, a differential advantage

During my years as President of Microsoft Spain, when I re-explained to any "visiting" executive what was the ONCE Social Group I realized how fortunate we are. In Spain we have a unique ecosystem: ONCE, the ONCE Foundation and Ilunion. The ONCE Social Group is already the fourth largest non-public employer in the country and the largest employer of people with disabilities in the world. For its part, Ilunion employs some 43,000 people, of whom nearly 39% are people with disabilities, and has established itself as a European benchmark in inclusive employability, with a presence in sectors as diverse as services, hospitality and the circular economy.

Inclusive training: leaving no one behind

The culture of inclusion and employability that Spain has cultivated is a huge asset. But globally, the AI revolution poses another challenge that we cannot postpone: empowering everyone to take advantage of this technology, leaving no one behind. In other words, accessibility to technology must come with accessibility to knowledge. According to the annual Microsoft Work Trend Index 2025 report, more than half of professionals consider AI training essential to maintain their employability, and nearly 60% expect their company to provide that training. This is a unique opportunity to equalize opportunities, especially for people with disabilities: the International Labor Organization (ILO) notes that only about 3 in 10 people with disabilities are active in the labor market globally. If we accompany the AI revolution with inclusiveskillingprograms, we will reduce the gap; if not, we will widen it. Investing in accessible AI training is no longer optional: it is key to making AI an equalizer of opportunities, not a new filter of exclusion.

Por supuesto, tan importante como formar a las personas es diseñar la tecnología pensando en todas ellas. ¿Qué pueden hacer líderes y equipos para lograr que la IA sea inclusiva desde su concepción?.

Five keys to inclusive design with AI

These recommendations - aimed at managers, product, innovation and technology teams - integrate best practices from UNESCO (2024), Accenture, the Microsoft Inclusive Design Toolkit, the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative, the World Economic Forum (2025) and the Forética Manifesto on Responsible and Sustainable AI (2025). They are further inspired by research from Harvard Business Review, MIT Sloan Management Review and Stanford Social Innovation Review on inclusion, digital ethics and responsible leadership.

Summarizing them, it would take too long to detail each point:

- Start with those who need it most. Design from the beginning with the users who face the most barriers: people who are blind, deaf, neurodivergent or have reduced mobility. Inclusive Design methodology (Microsoft) and HBR studies on inclusive innovation show that co-designing with these groups improves creativity and subsequent product adoption. Reference: HBR, "The Case for Inclusive Innovation" (2023).

- Accessibility by default, not by add-on. Configure features such as closed captioning, transcription or read aloud as active options from the start, not buried in menus. According to Accenture and W3C, incorporating accessibility as a "default" reduces downstream costs and expands the potential market. Reference: MIT Sloan Management Review, "Designing AI for Accessibility" (2024).

- Diverse and representative data. Inclusion starts in the data: incorporate atypical voices, images with technical aids (canes, hearing aids, etc.), low vision or mobility contexts. Collaborate with external partners and the ecosystem: startups or entities such as ONCE and Ilunion to avoid systemic biases and improve the quality of your product or service. Reference: HBR, "Building Fair and Inclusive AI Systems" (2024).

- Measure what matters: inclusion and autonomy. Don't just evaluate accuracy or speed, but user autonomy, effort reduction and real satisfaction. The World Economic Forum and MIT Sloan propose adding human impact metrics (equity, accessibility, well-being) to product KPIs. Reference: MIT SMR, "AI Metrics That Matter for People, Not Just Performance" (2025).

- Live and transversal governance. Align your IA policies with ethical frameworks (AI Act, ISO/IEC 42001, Forética Manifesto) and review compliance periodically. Create mixed committees - users, legal, data, design - and publish progress with transparency. Reference: Stanford Social Innovation Review, "From Ethics to Practice: Operationalizing Responsible AI" (2024).

On that day in 1995, when Bill Gates' screen was turned off, a change of outlook began within a company that decided to become one of the most advanced in terms of accessibility. Today, with the advent of artificial intelligence, that vision can - and should - be extended throughout the industry.

Because accessibility is not "an added function", it is a way of thinking and because when we open the door to those who find it more difficult, we all enter.

In the 1930s, in an interwar Spain and a Europe fascinated by the radio, the automobile and the airplane, Ortega y Gasset warned that technology should broaden our understanding of the world, not just speed up the results: "It does not consist in increasing speed, but in widening the range of the gaze" .

Today, that is also the task of artificial intelligence.

References:

- Forética (2025). Manifesto for a Responsible and Sustainable AI. Manifesto for a Responsible and Sustainable Artificial Intelligence - Forética

- Microsoft Inclusive Design Toolkit (2024). https://inclusive.microsoft.design

- Seeing AI: Seeing AI : Microsoft Garage

- Microsoft Work Trend Index 2025: The year the Frontier Firm is born

- W3C Web Accessibility Initiative. https://www.w3.org/WAI/

- World Economic Forum (2025). A Blueprint for Equity and Inclusion in Artificial Intelligence | World Economic Forum

- UNESCO (2024). Artificial Intelligence and Inclusion: Guidelines for Accessible Digital Futures. https://unesdoc.unesco.org

- Accenture (2023). The Disability Inclusion Advantage. https://www.accenture.com/content/dam/accenture/final/accenture-com/document-2/Disability-Inclusion-Report-Business-Imperative.pdf

- Speech Accessibility Project (2025). University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://speechaccessibilityproject.beckman.illinois.edu

- University of Michigan (2025). Enhancing Home-Based Physical Activity for Neurodivergent Children Using ChatGPT. Frontiers in Physiology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2024.1496114/full